Introduction

Federal nutrition programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) serve as an essential safety net for families experiencing poverty, food insecurity, and homelessness. In New York City nearly 18,000 families with over 30,000 children live in Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelters.1 Low-income New Yorkers, including those experiencing homelessness, spend a high portion of their limited income on essentials like food.2 Most households who use SNAP live below the federal poverty line, and the majority of benefits are distributed to those with monthly incomes at or below 50% of the federal poverty line.3 For example, a family made up of a single mom and two children at the federal poverty line (100%) brings in roughly $25,000 a year, and a family with the same composition living at 50% of the federal poverty line brings in $12,500.4 While there is no publicly available data on SNAP usage for NYC families living in shelter, analyses drawing on the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Family Options Study found that families experiencing homelessness are more likely than housed families living in poverty to receive SNAP benefits.5,6 Many families in shelter depend on SNAP benefits and other public food and economic assistance to help stabilize, which becomes even more critical when they exit shelter and need to pay for and maintain housing.7 However, the recently enacted federal H.R. 1 “One Big Beautiful Bill” Act (OBBBA) threatens to limit this vital support system for families experiencing homelessness and those at risk of homelessness.8

Key Takeaways

Families in shelter in New York City are at high risk of being impacted by the new federal SNAP policy due to several factors.

- High local enrollment in SNAP

- Funding changes that will make the program a budgeting challenge for New York State

- Rule updates that remove homelessness as a reason to exempt people from stricter work requirements

These impacts would include a reduction in SNAP benefits and a potential loss of benefits, intensifying obstacles to building economic and housing stability.

Background

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines food insecurity as “the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways.”9 SNAP has been one of the most effective tools in reducing food insecurity for householdsi throughout the United States.10 It is a federal entitlement administered by the USDA that provides low-income participants, including those who are homeless, with financial assistance for purchasing food.11 Around 12% of the total United States population or about 42 million people participate in SNAP.12 In New York State, 28% of all households that received SNAP benefits included at least one child.13 Members of families with children made up 52% of the total number of SNAP participants in New York State.14 Currently, nearly 1.8 million (~20%) New York City residents receive SNAP benefits, including 550,000 children.15

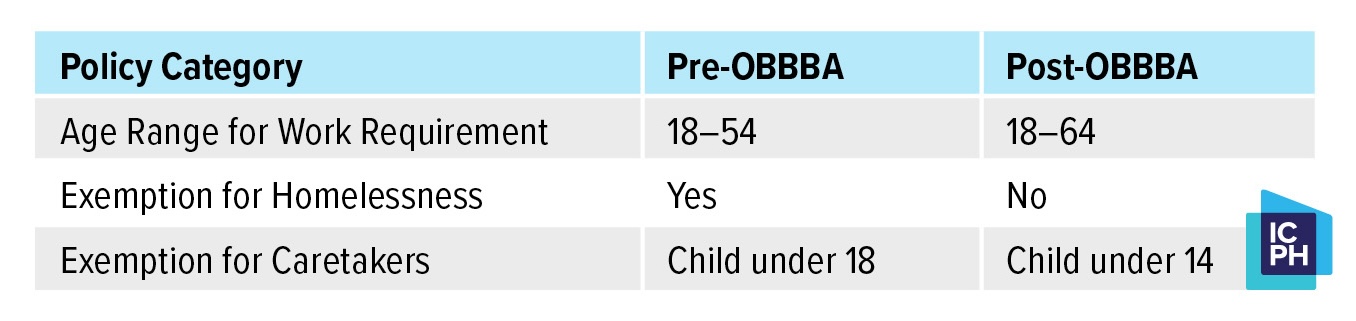

As part of OBBBA, specific changes made to SNAP could drastically affect families living in or at risk of entering shelter in New York City. These changes include shifting part of the cost burden for SNAP to New York State and reducing the cost-of-living increase that normally occurs to help recipients keep pace with the rising cost of food over time. One analysis found that 208,000 low-income families with children in New York could lose more than $25 a month in benefits—with an average reduction of $86 a month.16 There have also been changes to who will need to comply with additional work requirements previously reserved for “able-bodied adults without dependents,” referred to as ABAWD. While the name may be confusing because the connotation of a dependent is a minor under an adult’s care, these federal guideline exemptions have used this term “without dependents” in this context to describe people who only have dependent children ages 14 to 17 (See Table 1 for breakdown pre- and post-OBBBA). People who are experiencing homelessness who do not have dependents under the age of 14 will no longer be exempt from ABAWD work requirements under the OBBBA changes.17 In September 2025, the administration of Mayor Eric Adams estimated that 221,000 low-income NYC households would lose SNAP because of expanded work requirements.18

In November 2025, the federal shutdown that began October 1, 2025 caused additional pressures and confusion to recipients with SNAP benefits delayed, legal battles launched, and partial payments issued.19

Table 1 ABAWD SNAP Work Requirements Relevant to Families in Shelter Before and After H.R. 1 OBBBA Policy Changes

For more information see: USDA SNAP Provisions of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act of 2025

For more information see: USDA SNAP Provisions of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act of 2025

Food Insecurity and Participation in SNAP in New York City Remain High

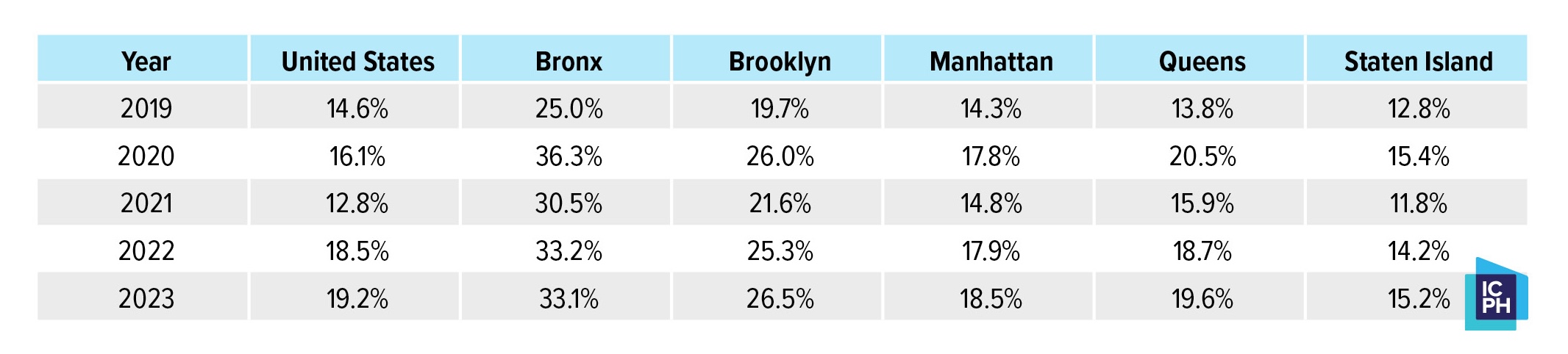

Food insecurity rates, especially among children, and SNAP participation, demonstrate that the need for assistance in New York City remains high among low-income families. In 2023, the national rate of child food insecurity increased to 19.2%, up from 14.6% in 2019. Three of the five boroughs, the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens, had rates greater than the national average (See Table 2).20

Table 2 Child Food Insecurity

Source: Feeding America “Map the Meal Gap Dashboard Years 2019–2023” https://map.feedingamerica.org/county/2023/overall/new-york/organization/food-bank-for-new-york-city.

Source: Feeding America “Map the Meal Gap Dashboard Years 2019–2023” https://map.feedingamerica.org/county/2023/overall/new-york/organization/food-bank-for-new-york-city.

In 2023, only Staten Island and Manhattan were below the national rate. Yet, it is important to note that Manhattan had the highest average cost per meal in the country: $6.09.21 SNAP benefits nationally and in New York City do not cover average meal costs.22 An even further reduction in benefits that ignores rising local food prices could be cause for alarm.

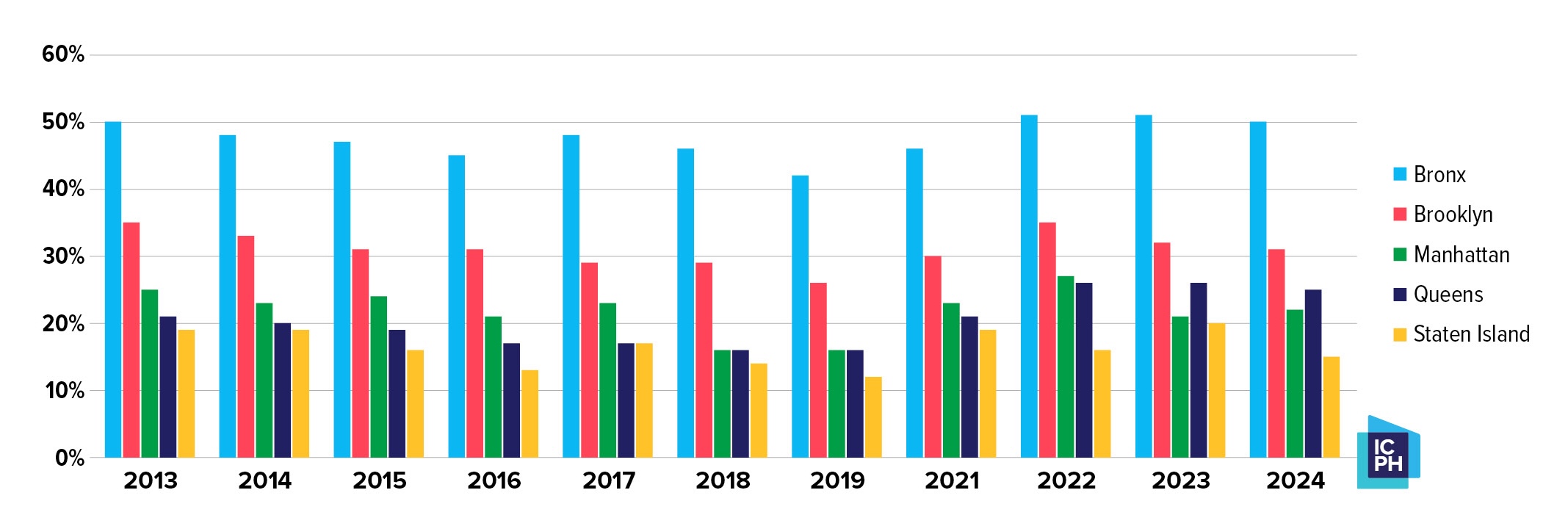

Even though SNAP was designed only to supplement costs, it is still widely used among New York City families with children. While SNAP can reduce food insecurity, enrollment in the program may be another indicator of need for supplemental income and economic assistance. Recent local enrollment among families with children was consistently highest in the Bronx and Brooklyn (See Figure 1). These areas are also the boroughs that had child food insecurity rates that were higher than the national average (See Table 2).

Analyses drawing on data from the Family Options Study found that from their sample, around 88% of families received SNAP benefits while in shelter.23 In New York City, families use their SNAP benefits while in shelter. Most DHS shelters for families with children have kitchenettes where families cook their own meals and purchase their own food. Many shelters also provide on-site emergency food pantries and referrals to local food banks to further supplement a family’s grocery supply. When families need to spend more time at food banks or direct greater parts of their income toward groceries, they are faced with competing priorities for other necessities like housing, whether they are currently living in shelter or struggling to make ends meet in the community.24

Figure 1 SNAP Enrollment in NYC Among Households with Children by Borough

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. “American Community Survey 1-year Estimates, 2013–2024 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables, Table S2201.” Data.Census.gov, 2025.ii

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. “American Community Survey 1-year Estimates, 2013–2024 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables, Table S2201.” Data.Census.gov, 2025.ii

New York State’s High Cost Burden Could Lead to Budgeting Challenges

Changes to SNAP through OBBBA include requiring states to share the cost burden for benefits for the first time (“state matching fund requirement”), which will increase the cost of administering the program to states.25 Previously, the funding for SNAP benefits was allocated by the federal government to New York State which then tasked municipal agencies, such as the Department of Social Services in New York City, with administering the program to residents. Going forward, part of the cost for benefits in addition to increased costs for administration will need to be funded from the state budget.

New York Governor Kathy Hochul, along with 22 other governors, signed a letter to Congressional leadership warning these increased state costs would cause limits to SNAP enrollment and unpredictability around long-term state budgeting due to a fluctuating annual state matching fund requirement.26 In New York, it is estimated that the annual state cost for SNAP could rise from nearly $500 million to $1.8 billion, a 272% increase.27 Changes to funding and spending in one area such as SNAP, could affect other areas such as homelessness response and cash assistance.28 Reduction in spending in these areas further limit the resources dedicated to families in shelter, which could lead to longer shelter stays and less support when families transition to permanent housing.29

Potentially 15% of Sheltered Children Could Be Impacted by Changes in SNAP Work Requirements

OBBBA extended SNAP new work requirements to people experiencing homelessness who have dependents ages 14 and over. Previously, people with children under the age of 18 who were experiencing homelessness were exempt from these work requirements.

About 15% or 5,175 out of 33,968 children in DHS shelters are between the ages of 14 and 17.30 The number of adolescents who may have younger siblings who exempt their parents from the new requirements is not captured by publicly available data, so the full scope of the impact remains to be seen.

Conclusion

The federal changes to SNAP come at a time when New York City faces an affordability crisis.31 Food insecurity and child food insecurity are high, with the prices of everyday family essentials from eggs to milk skyrocketing.

Sufficient food and housing are costly essentials for households, especially for extremely low-income and sheltered families with children. Policy makers in New York City and New York State are left with the difficult task of ensuring that these needs are met under severe budgetary constrictions that these new federal changes may inflict. At the time of writing, ongoing federal budget negotiations include a dramatic reduction in funding within HUD that could impact housing subsidy programs.32 City officials predict these federal changes will have ripple effects that will impact low-income families’ access to food and shelter.33 The dual reduction of federal support to house and feed families could prolong stays in shelter and jeopardize their ability to maintain housing after leaving shelter as families struggle more with economic stability.

References

1 New York City Department of Homeless Services. “DHS Daily Report.” NYC OpenData. August 22, 2013. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Social-Services/DHS-Daily-Report/k46n-sa2m/about_data.

2 Office of the New York State Comptroller. “The Cost of Living in New York City: Food.” April 2025. https://www.osc.ny.gov/files/reports/osdc/pdf/report-2-2026.pdf.

3 U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Evidence, Analysis, and Regulatory Affairs Office. “Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households: Fiscal Year 2023.” Edited by Aja Weston. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2025. https://www.fns.usda.gov/research/snap/characteristics-fy23.

4 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Annual Update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines, January 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1c92a9207f3ed5915ca020d58fe77696/detailed-guidelines-2023.pdf.

5 Burt, Martha, Jill Khadduri, and Daniel Gubits. “Are Homeless Families Connected to the Social Safety Net?” Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation (OPRE), 2016. https://acf.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/opre_homefam_brief1_hhs_participation_benefits_programs_033016_b508.pdf.

6 National Low Income Housing Coalition. “Homeless Families Use Key Safety Net Programs at Greater Rate than Others in Deep Poverty.” 2016. https://nlihc.org/resource/homeless-families-use-key-safety-net-programs-greater-rate-others-deep-poverty.

7 City Harvest and NYU Food Environment & Policy Research Coalition. “The Landscape of Food Insecurity and Housing Prices in New York City (NYC).” January 2025. https://www.cityharvest.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/The-Hidden-Cost-of-Living-A-Memo-on-how-Housing-Instability-Drives-Food-Insecurity-in-NYC.pdf.

8 U.S. Congress. “One Big Beautiful Bill Act.” 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/1.

9 U.S. Department of Agriculture. “USDA ERS – Measurement.” January 8, 2025. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement. Note: Definition used by USDA is from the Life Sciences Research Office, S.A. Andersen, ed., “Core Indicators of Nutritional State for Difficult to Sample Populations,” The Journal of Nutrition 120:1557S-1600S, 1990.

10 Ratcliffe, Caroline, Signe-Mary McKernan, and Sisi Zhang. “How Much Does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Reduce Food Insecurity?” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 93, no. 4 (July 2011): 1082–98. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4154696/.

11 U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).” February 20, 2025. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program.

12 Nchako, Catlin. “A Closer Look at Who Benefits from SNAP: State-By-State Fact Sheets; New York.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 21, 2025. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/a-closer-look-at-who-benefits-from-snap-state-by-state-fact-sheets#New_York. Note: Data from federal Fiscal Year 2024.

13 U.S. Department of Agriculture. “SNAP Household Characteristics Dashboard FY22: State-Level SNAP Overview,” Percent of SNAP households with individuals below age 18 (Fiscal Year 2022). 2025. https://www.fns.usda.gov/data-research/data-visualization/snap/household-characteristics. Note: This data aggregated data based on state reporting from federal Fiscal Year 2022.

14 Nchako. “State-By-State Fact Sheets; New York.”

15 New York City Department of Social Services. “Testimony of the NYC Department of Social Services, the Health & Hospital Corporation, and the Mayor’s Office of Federal Legislative Affairs.” New York City Council, September 15, 2025. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/hra/downloads/pdf/news/testimonies/2025/DSS-HRA-DHS-H-H-FLA-joint-testimony-on-Impact-of-Federal-Cuts-09-15-25.pdf. Note: Full hearing available through New York City Council https://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=7517346&GUID=E5A025C7-CE1E-4001-A4B6-1B3FFDE78A67&Options=&Search=.

16 Wheaton, Laura, Linda Giannarelli, Sarah Minton, and Ilham Dehry. “How the Senate Budget Reconciliation SNAP Proposals Will Affect Families in Every US State: A Summary of Preliminary Research Findings.” Urban Institute, July 2025. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2025-07/How-the-Senate-Budget-Reconciliation-SNAP-Proposals-Will-Affect-Families-in-Every-US-State.pdf.

17 U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Provisions of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act of 2025 – Information Memorandum.” September 4, 2025. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/obbb-implementation.

18 New York City Department of Social Services. “Testimony of the NYC Department of Social Services,” September 15, 2025.

19 Qiu, Linda. “SNAP Benefits Are Resuming as Government Reopens after Shutdown.” The New York Times, November 13, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/13/us/politics/snap-benefits-food-stamps-shutdown-update.html.

20 Feeding America. “Food Insecurity among the Child Population in the United States.” 2025. https://map.feedingamerica.org/county/2023/child.

21 Dewey, Adam, Julia Hilvers, Sena Dawes, Viginia Harris, Monica Hake, and Emily Engelhard. “Map the Meal Gap: A Report of Local Food Insecurity and Food Costs in the United States in 2023.” Feeding America National Organization, 2025. https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2025-05/Map%20the%20Meal%20Gap%202025%20Report.pdf.

22 U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)”; Waxman, Elaine, Poonam Gupta, Craig Gundersen, Rachel Kenney, Serena Lei, and Emily Peiffer. “Does SNAP Cover the Cost of a Meal in Your County?” Urban Institute, May 20, 2025. https://www.urban.org/data-tools/does-snap-cover-cost-meal-your-county.

23 Burt et al. “Social Safety Net.”

24 Kekatos, Mary. “Some SNAP Recipients Say They Have to Choose between Rent and Food amid Halt in Benefits.” ABC News, November 6, 2025. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/snap-recipients-choose-rent-food-amid-halt-benefits/story?id=127235340.

25 New York Office of Comptroller. “Federal Actions Threaten to Exacerbate Rising Food Insecurity.” July 2025. https://www.osc.ny.gov/files/reports/pdf/epi-federal-actions-threaten-to-exacerbate-rising-food-insecurity.pdf.

26 Governors of 26 States. Letter to Congressional Leadership Regarding Proposed SNAP Cost Shifts. June 24, 2025. https://governor.nc.gov/june-24-2025-letter-governor-stein-and-governors-across-country-congressional-leadership-proposed/open.

27 Villa, Miguel, and Stephanie Scott. “SNAP Changes Will Upend State Budgets.” Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality, September 29, 2025. https://www.georgetownpoverty.org/issues/snap-changes-will-upend-state-budgets/.

28 De Jesús-Szendrey, Mariana. “SNAP under Attack: What Federal Cuts to Food Aid Would Mean for NYC.” City Limits, June 30, 2025. https://citylimits.org/snap-under-attack-what-federal-cuts-to-food-aid-would-mean-for-nyc/.

29 Ibid.

30 New York City Department of Homeless Services. Population Average Daily Census: Individuals in Shelter DHS Data Dashboard—Fiscal Year 2025 Q3. 2025. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/dhs/downloads/pdf/dashboard/tables/FY25-Q3-DHS-Data-Dashboard-Data.pdf.

31 Yera, Christopher, Ryan Vinh, Yajun Jia, and Schuyler Ross. “Data Snapshot: How Is the Rising Cost of Living Impacting New Yorkers?” Robin Hood, September 12, 2025. https://robinhood.org/reports/poverty-tracker-data-snapshot-inflation-nyc/.

32 Love, Henry O., and Jade Vasquez. “The Cost of Cuts: The FY26 Federal Budget, Disinvestment and the Rising Risk of Family Homelessness in New York.” Win, September 2025. https://winnyc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/The-Cost-of-Cuts_-Federal-Disinvestment-and-the-Rising-Risk-of-Family-Homelessness-in-New-York_FINAL.pdf.

33 De Jesús-Szendrey. “SNAP Under Attack.”